Standing in a classroom at University of Toronto Schools in the spring of 2004, global education consultant Dr. Michael Fullan, former Dean at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE), uttered one of his most memorable lines. “People only call me a guru, ” he joked, “because they can’t spell charlatan.” Appointed, for a second time, as a Senior Education Advisor to the Ontario government (2004-2018), he was in a buoyant mood after being welcomed back from a a period of exile (1997 to 2004) guiding Tony Blair’s New Labour education reforms.

Today, sixteen years later, the global education consultant still ranks 20th out of the top 30 “Global Education Gurus” as posted annually by All American Entertainment (AAE), the Durham, NC-based speakers’ bureau. Michael Fullan, O.C., now billed as Global Leadership Director, New Pedagogies for Deep Learning, still commands fees of $10,000 to $20,000 for his North American speaking engagements.

Now considered “a worldwide authority” on education reform, he occupies considerable territory in Education Guru Land. Preaching system-wide reform, advising ministers of education, and mingling with thought leaders, he’s far removed from the regular teacher’s classroom. He’s also more likely to be found in the company of other members of the pantheon, TED Talk legend Sir Ken Robinson (#8), school leadership expert Andy Hargreaves (#21), and Finnish education promoter Pasi Sahlberg (#28).

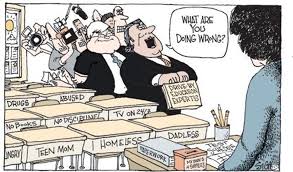

The world’s leading education gurus seem to have had a hypnotic effect on policy-makers and superintendents in the entire K-12 education sector. The profound influence of Fullan and his global reform associates is cemented by an intricate network of alliances which, in the case of Ontario, encompasses the Council of Directors of Education (CODE), the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE), the Ontario Principals’ Council (OPC), and a friendly parent organization. People for Education.

Challenging the hegemony of this entrenched educational change establishment is a formidable undertaking. “Teacher populism” inspired by British teacher Tom Bennett and exemplified in the spontaneous eruption of researchED from 2013 to 2018 made serious inroads, particularly in Britain, Western Europe, and Australia. It faced stronger headwinds in the United States and Canada, where the progressive education consensus is more all-pervasive. The fear and panic generated by empowered teachers (working around education schools) has sparked not only seismic reactions, but the closing of ranks.

Challenging the hegemony of this entrenched educational change establishment is a formidable undertaking. “Teacher populism” inspired by British teacher Tom Bennett and exemplified in the spontaneous eruption of researchED from 2013 to 2018 made serious inroads, particularly in Britain, Western Europe, and Australia. It faced stronger headwinds in the United States and Canada, where the progressive education consensus is more all-pervasive. The fear and panic generated by empowered teachers (working around education schools) has sparked not only seismic reactions, but the closing of ranks.

One of the most recent responses, produced by Cambridge University School of Education lecturer Steven Watson, attempted, not altogether successfully, to paint “teacher populism” as a movement of the New Right and offered up a piece of Twitter feed ethnography smacking of contemporary “cancel culture.” That article completely ignored the fundamental underpinning of researchED — the crowds of educators attending Saturday PD conferences, paying your own registration fees, and engaging with teacher-researchers who speak without remuneration.

Curiously absent from Watson’s article was any reference to dozens of top-notch researchED speakers, including British-born student assessment expert Dylan Wiliam (#11 – 2020 – $10,000-$20,000), AFT magazine cognitive psychologist Dan T. Willingham, and How to Learn Mathematics specialist Barbara Oakley, who regularly speak without remuneration at such conferences.

researchED emerged to fill a gaping hole in K-12 teacher development. The researchED conference Model is decidedly different. Conferences are held on Saturdays in schools rather than hotel conference centres. Two dozen or more teacher researchers or practicing teachers are featured presenting in actual classrooms. researchED events showcase speakers reflecting a wide range of perspectives, spark lively pedagogical debates, and are increasingly diverse in their composition. Many of the short 45-minute presentations by volunteer presenters focus on contested curricular or pedagogical issues, including education myths, explicit instruction, cognitive load, early reading, mathematics skills, and teacher assessment workload.

Over 45,000 teachers on four continents attended dozens of researchED events over the seven years before COVID-19 hit us with full force. The London-based teacher research organization publishes its own bi-annual free magazine and is producing, in collaboration with John Catt Educational Publishing, a series of researchED guides to the latest evidence-based research. Since April 2020, the movement has continued with free virtual PD conferences under the banner of researchED Home.

Today’s education world is full of high-priced speakers who are featured at state, provincial and regional professional development conferences, mostly at events where the registration fees are many times higher than that of a researchED conference anywhere in the world. Dr. Fullan’s speaking fees pale in comparison with more messianic gurus such as Harlem Children’s Zone founder Geoffrey Canada ($50,000 – $100,000) and global tech researcher Sugata Mitra (#19 –$30,000 – $50,000), but he still commands fees comparable to American public school champion Diane Ravitch (#1 -2020), OECD Education director Andreas Schleicher, progressive education advocate Alfie Kohn, and Alberta ed tech innovator George Couros.

Almost forty years since the the publication of The Meaning of Educational Change (1983), Fullan’s real influence is reflected in the missionary work of his extensive Educational Change entourage, including Pearson International advisor Sir Michael Barber, Welsh education change professor Alma Harris, former York Region superintendent Lyn Sharratt, and OISE School Leadership professor Carol Campbell.

Although Dr. Hargreaves was mentored by Fullan at OISE, he’s branched out and, while at Boston’s Lynch School of Education, generated (with colleague Dennis Shirley) an interconnected network of his own. The Fullan-Hargreaves educational change constellation sustains two academic journals and is closely aligned with two American educational enterprises, Corwin Educational Publishing and PD resource provider Solution Tree. That alliance has produced a steady stream of books, articles and workshops inspired by the global school change theorists.

The prevailing educational reform consensus has largely gone unchallenged for the past few decades. Reading Steven Watson’s thinly-veiled academic assault on “teacher populism” demonstrates how little it takes to rattle the cage of the ideologues actively resisting teacher-driven research, the science of learning, and challenges to current pedagogical orthodoxy. Equipping today’s classroom teachers (and learners) with what the late American education reformer Neil Postman once termed “built-in shockproof crap detectors” is as threatening now as it was a few decades ago.

What sustains the hegemony of today’s educational reform establishment? How much of that controlling influence is perpetuated by education gurus committed to upholding the prevailing consensus and defending a significant number of uncontested theories? Will the recent COVID-19 education shutdown change the terms of engagement? Should “teacher populism” be dismissed as subversive activity or approached as a fresh opportunity to confront some of the gaps between philosophical theory and actual classroom practice?

School system leaders and their provincial ministers tend to embrace broad, philosophical concepts like

School system leaders and their provincial ministers tend to embrace broad, philosophical concepts like

Middle-school teacher David Stocker, author of the textbook

Middle-school teacher David Stocker, author of the textbook