New Brunswick disabilities advocate Heather Chandler, the mother of a hearing-challenged daughter, is no fan of the what she describes as the “illusion of inclusion.” On an April 2023 CBC NB radio panel of parents, she described what it’s really like for her daughter Alison and far too many other children in New Brunswick’s one-classroom-for-all model.

Social isolation, anxieties and frustrations are an everyday school experience for many children. That’s what vocal N.B. parents such as Chandler are saying publicly, some for the first time. It all surfaced during the tension-filled consultations over the aborted French language reforms threatening the French immersion program

Chandler is far from alone in speaking out about how it’s adversely affecting her own daughter and children with disabilities of all kinds. “She’s holding it in,” Chandler says, while others are “blowing up in class” causing disruptions. It all comes out when she gets home. “For deaf kids, it’s actually exclusion.” In short, “it’s not working.”

Chandler’s daughter displays the classic behaviour of what are known as “Coke bottle kids.” That term, coined by American education observer Jay Elizabeth Brownlee, originally used to describe neurodivergent children, has far wider application. It helps to explain why teachers say school kids are “fine” or “had a good day” yet the second they get home (or before they leave the school parking lot), they simply “blow up in your face.”

Chandler and that CBC NB panel, including Moncton parent Clinton Davis and French immersion parent Weh-Ming Cho, identified, in considerable detail, how challenging it can be trying to cope in today’s classrooms. Each of them, to varying degrees, supported structural changes building-in more “fluidity” for kids, including a broader range of options to ensure meaningful inclusion for most, if not all kids, right across the spectrum.

Student behaviour and the remarkably rigid N.B. inclusion model are intimately connected. Investing some $30-million more may provide some temporary relief, but it’s not getting to the root of the matter. Without some fluidity in movement, it can be, in Chandler’s words, “an isolating experience.”

Listening to his children, Moncton’s Clinton Davis got a good sense of what’s actually going on in different schools. His kids simply don’t feel like the regular teachers know how to support students with disabilities nor do they have the resources to manage students with behavioural problems. Some unruly students, he pointed out, do not have diagnosed disabilities and are simply ‘acting up’ and disrupting classes.

While French immersion classes run more smoothly, Cho thinks they too might benefit from some variation in delivery models, including enrichment opportunities. Allowing students to periodically interact with “new faces” might provide some relief as long as it’s not perceived as punishment of any kind. Being stuck with the same people all day, whatever your age, he added, could become a “hellscape” for anyone.

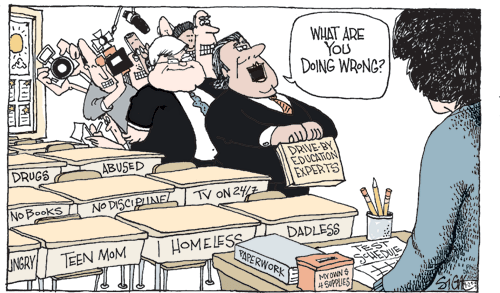

The latest provincial plan to address student behaviour challenges, announced in late July by NBTA Executive Director Ardith Shirley and Assistant Deputy Education Minister Tiffany Bastin, came up considerably short. Hiring “behaviour mentors” and adding contract supply teachers was presented as a “near-term” response. It looks far more like a band-aid to patch-up the existing model and quell rising parent and teacher concerns.

Education Minister Bill Hogan’s statement supporting the latest plan sounded like it was simply a matter of providing more classroom supports. The behaviour intervention mentors, he said, were aimed at helping students “learn to self-regulate” and helping staff to “co-regulate” guiding students on a “more positive path” and “reduce interruptions that happen in class.” Assigning supply teachers to specific schools, Hogan added, provided more predictability for teachers and consistency for learning-challenged children.

A year ago, former N.B. Education Minister Dominic Cardy was preparing to revamp thar province’s rather rigid inclusion model to address the incidence of behavioural disruptions. The policy change, he wrote, was aimed at “making it clear that we defined inclusion as being inclusion within the school, not the classroom.” That meant all students would be included in the class unless and until the behaviour of a single student disrupted the entire class. In such cases, that student would be provided with an alternative placement with resource support.

Sarah Wagner, executive director of Inclusion N.B., strongly objected to any plan deviating from Policy 322 on Inclusive Education, claiming that inclusion should continue to mean every student, all the time, without exception. “The right of the child is to be with their peers and within the classroom,” she told CBC News. “The way we need to look at it is — what supports are required to make that successful.”

The interim report issued by in June 2023 by Shirley and Bastin backs away from that inclusion reform commitment. It tilts more in the direction of maintaining the status quo, in line with the position of Inclusion NB, formerly known as the Association for Community Living.

New Brunswick’s “Coke bottle kids” are not really integrated into those classrooms and some are disruptive because teachers are overwhelmed and unable to cope with the frequency of class disruptions. When disruptions occur, teachers simply keep the lid on or evacuate everyone except the student acting out and causing a disturbance.

Legitimate parent concerns about disruptive students and the social isolation of kids with disabilities in regular classes are not really being addressed. New Brunswick has settled for What Cardy described as “ rhetorical inclusion” and it’s not only an “absurd situation” but not sustainable for much longer. Let’s hope this isn’t widespread in our provincial school systems.

- Extracted and adapted from an Education Beat column, Telegraph-Journal, September 23, 2023.

What is “meaningful inclusion for so-called “Coke-Bottle Kids”? Why are today’s teachers so overwhelmed by students with complex needs and struggling to maintain safe, calm and mutually cooperative class environments? Is adding “behaviour mentors” going to make much of a difference? How many adults can a regular classroom teacher manage along with a class of kids? Where might policy-makers look to find a school system where severely challenged kids are identified, supported and integrated back into the mainstream classroom?