Implementing true inclusive education is one of the most formidable challenges facing Canadian provincial school systems. Scanning the Inclusion and Special Education policy landscape from province to province, New Brunswick stands out as an outlier. The so-called “New Brunswick Model” adopted in 2006 and formally confirmed in 2012-13 focuses almost exclusively on integrating all students into regular or mainstream classes.

Education Minister Dominic Cardy’s recent announcement of a New Brunswick inclusion policy review was welcomed by concerned parents and teachers. Defenders of the existing inclusion model under Policy 322 reacted with dismay and trepidation, and for good reason. Public consultations have revealed, once again, that the total inclusion classroom is not working for every student nor for far too many regular teachers. While former Education Minister Jody Carr and his entourage are travelling the world promoting that model, it is on decidedly shaky ground at home.

Education Minister Dominic Cardy’s recent announcement of a New Brunswick inclusion policy review was welcomed by concerned parents and teachers. Defenders of the existing inclusion model under Policy 322 reacted with dismay and trepidation, and for good reason. Public consultations have revealed, once again, that the total inclusion classroom is not working for every student nor for far too many regular teachers. While former Education Minister Jody Carr and his entourage are travelling the world promoting that model, it is on decidedly shaky ground at home.

Everyone today supports inclusive education and there can be no turning back. Societal changes, human rights advocacy, and the growing complexity of classrooms in terms of capabilities, language, race, ethnicity and gender have combined to forge a broader commitment to truly inclusive education.

What looked progressive fourteen years ago when Wayne MacKay proposed the current N.B. inclusion model has now been superseded by newer, more flexible and more responsive approaches better suited to meeting the full range of student needs. We are also now more attuned to significant differences on the question of how to achieve meaningful, properly-resourced inclusion for all students across the full spectrum of abilities.

A lot is at stake in the latest review of inclusive education policy. That is because the so-called ‘New Brunswick Model’ is a provincial export product and is being considered for implementation in Ireland. An October 2019 report from the Irish National Council on Special Education (NCSE), heavily influenced by Carr’s policy advocacy, tilted in the direction of adopting a ‘total inclusion model’ and it has inspired a fierce debate in Ireland.

The proposed policy reform has put New Brunswick education under the microscope. No other Canadian province has chosen to follow the N.B. inclusion path, and this has been duly noted by vocal critics of the whole scheme in the widely-read Irish Times newspaper.

Much has been made of UN Special Rapporteur Catalina Devandas-Aguilar’s commendation of New Brunswick for its compliance with international human rights declarations. That was, it must be noted, one of the only positive mentions in her report which critiqued almost every other province for their ‘uneven application’ of policies across all public services, including heath, education, housing and transit.

Many educators and researchers in Ireland are puzzled as to why the N.B. model emerged as a preferred option when it is at odds with inclusive policy elsewhere. Most provinces, including neighbouring Nova Scotia, offer ‘inclusive education’ with options ranging from integration into regular classrooms to special ‘resource’ classes to specialized programs in alternative school settings.

Defenders of the N.B. model were rocked a year ago by a series of Toronto Globe and Mail investigative stories focusing on whether “inclusive classrooms” were working for most if not all students. The deeply moving story of Grayson Kahn, a 7-year-old Ontario boy with autism excluded from his school for assaulting an Education Assistant, captured nation-wide attention. It also departed from the usual script – extolling the virtues of inclusion – and, instead, raised serious questions about the difficulties of accommodating children with complex needs in regular classrooms.

Defenders of the N.B. model were rocked a year ago by a series of Toronto Globe and Mail investigative stories focusing on whether “inclusive classrooms” were working for most if not all students. The deeply moving story of Grayson Kahn, a 7-year-old Ontario boy with autism excluded from his school for assaulting an Education Assistant, captured nation-wide attention. It also departed from the usual script – extolling the virtues of inclusion – and, instead, raised serious questions about the difficulties of accommodating children with complex needs in regular classrooms.

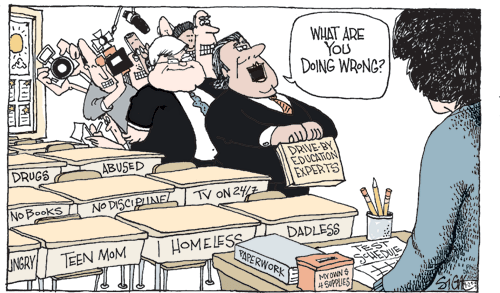

Teachers in Canada, including many in New Brunswick, are reporting a dramatic rise in violent incidents disrupting their classrooms, and rising tensions with families who feel their regular stream children are at risk. For the past five years, periodic concerns have been voiced by the New Brunswick Teachers Association (NBTA) over threats to the safety of teachers and education assistants.

Some educators in the Globe and Mail series addressed the so-called ‘elephant in the classroom,’ daring to wonder if inclusion has gone too far for students with very complex needs. Inclusiveness will not work, they claimed, without “a thoughtful rethinking of how we teach children with diverse needs and how we structure the school day.”

School districts in Canada are beginning to acknowledge the need for “time out rooms” to allow students experiencing meltdowns space and time to recover. Families with children who have intellectual and developmental disabilities are increasingly being asked to pick up kids early, start the school day later or simply keep them home for the entire day.

Complicating matters is the fact that apart from a few advocacy or parent group surveys, most Canadian school districts, including those in New Brunswick, didn’t formally track these exclusions or shortened days until recently mandated to do so.

The N.B. inclusion system is full of holes, judging from concerns raised by parents and teachers during Minister Cardy’s current round of consultations. Co-founder of Riverbend Community School in Moncton, Rebecca Halliday, was one of those speaking up for changes. She has fought an uphill battle for five years to establish a school for severely learning challenged students. Her struggles mirror those of hundreds of parents and families effectively ‘excluded’ by the total inclusion classroom policy and practice.

Conducting a provincial review opens the door, once again, to providing support for the most severely challenged students and need relief for their exhausted parents. What Halliday’s school struggle amply demonstrates is that it will not happen in New Brunswick without the introduction of a tuition support program being extended to students and families without the means to pay the tuition themselves.

Conducting a provincial review opens the door, once again, to providing support for the most severely challenged students and need relief for their exhausted parents. What Halliday’s school struggle amply demonstrates is that it will not happen in New Brunswick without the introduction of a tuition support program being extended to students and families without the means to pay the tuition themselves.

Such a program exists in Nova Scotia where, since September 2004, provincial education authorities have offered a Tuition Support Program (TSP). It not only plugged the service gap, but broadened public access to intensive support programs designed for students with acute learning difficulties. Under the TSP, a small number of private, independent Special Education schools (DSEPS) (Grade 3–12) not only exist, but fill the gap by providing a vitally important lifeline in the continuum of student support services.

Inclusion is an ideal to which most advanced education countries, provinces and states aspire. One of the best and most influential international statements, the Salamanca Statement on Principles and Practice in Special Needs Education (UNESCO 1994), continues to inform much of the current policy on inclusive education. Children should be learning together in schools – but not necessarily in one particular setting.

With the exception of New Brunswick, provincial ministries of education take their cue from the Salamanca Statement and are working toward inclusive education by removing barriers and improving student supports across a range of program service options, including intensive support for children with the most complex needs. Today, inclusive education is the overriding philosophy and the real challenge is to ensure that students, parents, and service providers find the ‘right fit’ for every child or teen.

Winning a September 2016 Zero Project prize and recent praise from a UN agency, it turns out, is a dubious honour for New Brunswick because it involves expending so much time and energy defending a regular class setting for everyone, when some fare far better in smaller classes with more intensive resource support and others thrive with more individualized attention.

Instead of merely complying with a UN philosophical declaration, Minister Cardy and the Department would be better advised to study carefully the findings of Nova Scotia’s 2018 Inclusive Education Commission and its prescription. Following that extensive and comprehensive review, Nova Scotia is now fully engaged in building a multi-tiered system of support (MTSS), much better aligned with best practice and evidence-informed research.

- An earlier version of this post appeared in the Telegraph-Journal, March 5, 2020.

Tackling inclusion stirs up passions and raises sensitive issues, but it’s time to address the key policy questions: Will the New Brunswick Model ever work, given the complex challenges in today’s classrooms? What are the real and unintended consequences of mandatory inclusion in the absence of other viable, attractive or effective alternatives? Is the properly-resourced all-inclusive classroom model feasible or sustainable? If the N>B. model is optimal, why are school districts everywhere tilting more in the direction of implementing MTSS and attempting to support everyone across the full continuum of needs?

While Director Malloy ‘walked back’ from that particular TDSB Enhancing Equity Task Force recommendation, it was abundantly clear that TDSB under Malloy is prepared to stand firm on implementing its own version of “enhancing equity” for all students. That’s also perfectly consistent with Malloy’s stance while serving as Director of the Hamilton Wentworth District School Board from 2009 to 2014. As a chief superintendent, he’s well known for putting in motion “educational equity” projects that seek to limit school choice in public education and threaten the existence of specialized program schools.

While Director Malloy ‘walked back’ from that particular TDSB Enhancing Equity Task Force recommendation, it was abundantly clear that TDSB under Malloy is prepared to stand firm on implementing its own version of “enhancing equity” for all students. That’s also perfectly consistent with Malloy’s stance while serving as Director of the Hamilton Wentworth District School Board from 2009 to 2014. As a chief superintendent, he’s well known for putting in motion “educational equity” projects that seek to limit school choice in public education and threaten the existence of specialized program schools.