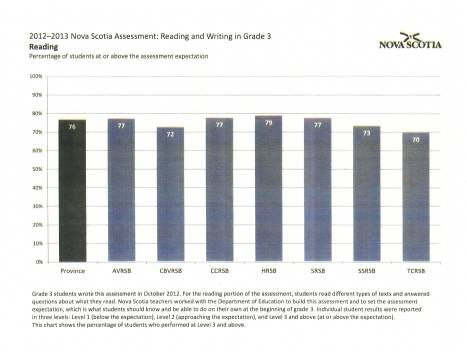

Teaching kids to read and write are two of the highest priorities of our schools. Since September of 2023, Nova Scotia has begun to tackle early literacy with the rollout of a structured literacy strategy based upon a framework known as the “Six Pillars of Effective Reading Instruction.” Sounding out words, we know from the science of reading, is essential to cracking the code and beginning to read.

Knowing something about a topic takes you to the next level. Truly discovering the world of dinosaurs is enhanced by knowing about pre-historic times; grasping the meaning of fables requires some appreciation for the magic of myth and legend; and encountering a nursery rhyme may eventually help in appreciating a sonnet.

This fundamental truth was driven home in one of the best-selling books of 2019, The Knowledge Gap, written by American education journalist Natale Wexler. In it, the Washington DC-based writer claimed that the so-called “skills gap” in North American education was actually driven by, as the title states, a gap in knowledge.

Distilling it down to a simple axiom, “the more kids know, the better they read.” That’s the core message that Wexler will bring to Saint Mary’s University on November 4 in her keynote address to the upcoming Cross-Canada researchED “Closing the Learning Gap” conference. While there, she may be challenged by a few of the other baker’s dozen of presenters who remain to be convinced that “knowing stuff” is as central to teaching reading in our schools.

Elementary schools tend to send-off a positive vibe and Wexler raised a few hackles by identifying mostly unrecognized deficiencies in prevailing curriculum and teaching practices. Since elementary school instruction focused on teaching ‘reading strategies’ in ‘learning blocks’ rather than ‘reading to learn,’ she pointed out that knowing the background, or prior knowledge, was absolutely critical to comprehension and a matter of social justice, opening new doors to disadvantaged students.

Following-up in widely read articles for The Atlantic and Forbes magazine and more recently on her “Knowledge Matters” podcasts, Wexler brought her personal journey into the science of reading to a wider audience. “Kids actually love to learn stuff. They love to feel like they’re experts. It does wonders for their self-esteem,” she says. “Once teachers try it and can see what can happen…they’re going to say ‘I’m never going back to what I was doing before.”

Here in Halifax Wexler’s keynote address will seek to connect the dots between reading comprehension and writing. Instead of doubling down on student assessment prep and practicing skills like “finding the main idea,” she will demonstrate that students often learn to read through exposure to sometimes unfamiliar texts in social studies and science classes. The more successful schools, she notes in her pre-talk description, are “taking deeper dives into topics and calling upon students to write about their discoveries with promising results”

Nova Scotia’s curriculum lead for Six Pillars implementation Andrew Francis, who led a recent literacy transformation at New Glasgow Academy, is another key presenter. Dr. Francis will be modelling a school-based approach to teaching foundational word reading skills. He plans to share lessons learned in leadership and in collaboration with teachers in revamping approaches to literacy instruction and assessment.

Reaching all students can be a formidable challenge in elementary classes, and particularly those from African-Nova Scotian communities. “Culturally-relevant pedagogy” (CRP) and engaging learning materials that resonate with Black children may provide a key to advancing early literacy in many schools. St. Francis Xavier University education professor Dr Wendy Mackey’s presentation will demonstrate why “CRP” lessons cannot be purchased off-the-shelf and simply delivered to students.

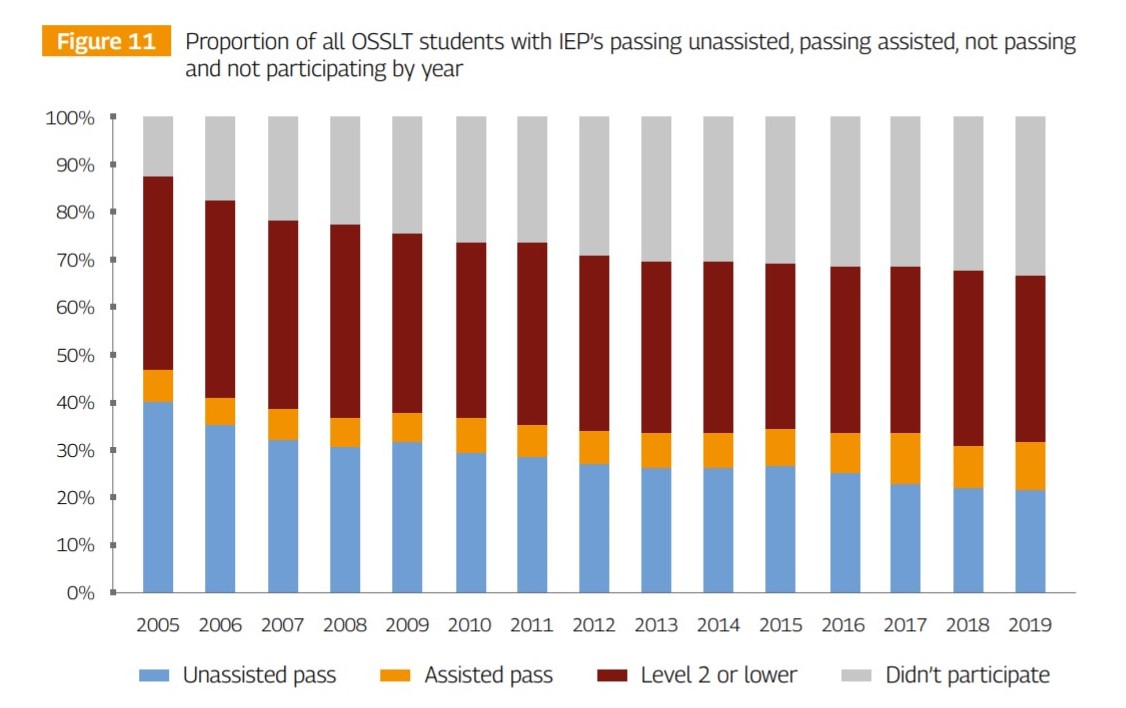

Leading expert on teaching early reading, Jamie Metsala, Learning Disabilities Chair at Mount Saint Vincent University, can be expected to respond to Wexler’s message, offering a slightly different twist on improving reading comprehension. “Vocabulary and knowledge are important for understanding texts and for academic achievement,” Metsala says, and the two do belong together. That’s confirmed in a recent study in Reading and Writing (December 2022) demonstrating that building “vocabulary knowledge” was critical, especially in supporting adolescent students struggling with low levels of achievement.

Dr. Metsala plans to share her latest research on what works in the classroom. Teaching Grade 1 and 2 students with “researcher-developed English Language Arts (ELA)-science units” provides a promising way of serving students with lower initial vocabulary-knowledge and for students learning English as an additional language. The teaching units themselves and teachers’ experiences will be presented as will the complexities and challenges of teaching elementary language arts.

Out west, in Vancouver, Dr. Kathryn Garforth anchors the Cross-Canada researchED program with a keynote address on “The Importance of Applying Research to Practice in Literacy Instruction.” Based upon her own Ph.D. research and best practice in aligning structured literacy into classroom instruction. We will see why Dr Garforth is the leading champion of the Right to Read Initiative in British Columbia.

So, what’s the answer to the fundamental question posed in this commentary? Embracing the science of reading is critical, but so is being attuned to the complexities of teaching in today’s elementary classrooms, and seeing the value of “culturally-relevant” strategies and materials in reaching all of our students. Hopefully this has piqued your curiosity and you may be encouraged to join us for Cross-Canada researchED (Nov 4, 2023) at Saint Mary’s University or Kenneth Gordon Maplewood School in North Vancouver. Classroom teachers, literacy tutors, researchers and interested parents are particularly welcome and to view the sessions later on our researchED Canada News YouTube channel.

*An earlier version of this commentary appeared in The Chronicle Herald/ Saltwire News, Oct. 27, 2023.

What is the key to building comprehension once students have mastered the fundamentals? How important is knowing something about a topic? Should early reading programs be better integrated into a braoder reading-intensive program integrated into social studies and science? Do we need a much-enhanced core knowledge curriculum which opens doors and sparks curiosity about new and unfamiliar topics?