Students in Canada’s K-12 schools have not bounced back. My latest report, Pandemic Fallout: Learning Loss, Collateral Damage, and Recovery in Canada’s Schools, (Cardus, November 29, 2023) identified the root of the problem and challenged governments, educators, and parents to recognize and respond to the deep and lasting effects of pandemic disruptions on education.

A week later, my essential analysis and conclusions were borne out in the latest Program of International Student Assessment (PISA) report (December 5, 2023) testifying to the serious decline in the performance of Canadian students in mathematics, reading and science from 2018 to the end of 2022.

Nearly four years after the first COVID outbreak, my report shrugged-off the prevailing ‘pandemic fatigue’ and tackled a few important questions: How much learning loss have students suffered, and how can we respond? How did the pandemic impact students’ social development and mental health? How was the response of schools different across the educational spectrum? How can we do things better next time?

What happened during the education disruption? Surveying the comprehensive, albeit admittedly dense, heavily footnoted study, these were the essential findings:

- Learning loss is real, and a substantial learning deficit arose early in the pandemic and has persisted over time.

- The ‘knowledge gap’ is affecting students from elementary grades through high school, and is more pronounced in mathematics than in reading.

- Children with special needs and those from marginalized communities suffered the most and continue to do so.

- As many as 200,000 Canadian students went missing from school at the height of the first COVID-19 wave of infections.

- Lower-income families were disproportionately affected, increasing the knowledge gap between students from affluent households and those from disadvantaged households.

- Smaller and more autonomous schools fared better and provided more consistent, mostly uninterrupted, learning.

- No one emerged unscathed and but students in some settings were cushioned, challenged, and better supported.

Canadian provincial and district education authorities, the report demonstrates, were caught completely off-guard by the pandemic crisis, minimized the potential impact of prolonged school closures, abandoned system-wide student testing and generated little or no data on its impact on students, teachers, or families. Compared to most other OCED countries, Canada suffered from what I termed “data starvation” – flying blind though the pandemic while closing schools for extended periods of time, averaging 130 lost days (more than 25 weeks) from province-to-province across Canada (UNESCO 2023).

Large-scale assessment research—which is used to draw reliable and comparative measures of student achievement and system-level judgments—was either suspended or limited during the pandemic across Canada. This is both shocking and critical, as without the benefit of aggregated student data, researchers and policy-makers are left to piece together the pandemic’s impact on student achievement. Importantly, this has damaged Canada’s longstanding reputation as a global leader in education.

Instead of stopping with a diagnosis, the report does review best practice in implementing immediate learning recovery programs and in addressing the critical need for a broader future ‘education crisis’ response strategy.

Best Practice in Implementing “Catch-Up” Initiatives

Recognizing the problem is the first step, but tackling learning recovery is a greater challenge. Three immediate responses come highly recommended by leading experts (Srivastava, 2021, McKinsey & Company, 2020):

- Revamp the entire K–12 curriculum to facilitate students catching up.

- Focus on the core competencies of reading & literacy as well as pro-social skills.

- Initiate targeted interventions, including intensive tutoring & summer catch-up sessions.

Best Strategy for Longer-Term Recovery

First and foremost, Canadian education ministers and school leaders need to be much better at tapping into research and strategies from elsewhere, and, in particular, from leading systems and research institutes in the EU, the UK, and the United States.

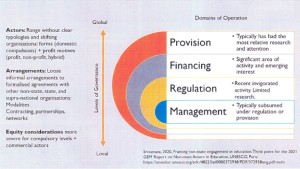

Our overall strategy, modelled by UNESCO and World Bank researchers, should be informed by a “crisis-sensitive approach” (Srivatava, 2021). Effective, evidence-based pandemic educational-policy planning recovery should involve four key considerations:

- managing a crisis and instituting first responses

- planning for (interrupted) reopening with appropriate measures

- sustained crisis-sensitive planning, with considerations of assessing risks for the most vulnerable

- adjusting existing policies and strengthening policy dialogue

Most important of all – break down the silos and get to the heart of the problem. Cage-busting leadership will be needed to disrupt established routines jealously guarded by the institutional gatekeepers. Collective planning exercises with cross-sectoral collaboration and community engagement from marginalized groups should be a sustained part of pandemic-recovery planning exercises.

Conclusion: Prepare Now for the Next Global Disruption

Consistent, reliable, and evidence-based data is needed if we are to effectively respond to the full range of the pandemic’s longer-term impacts on children, teachers, and families. A new Canadian education-research agenda will be necessary for that to happen. Tackling pandemic learning loss, tracking student progress, and getting students back on track are of vital and immediate strategic importance because we are still engaged in a recovery mission, with no room for complacency. Those are the biggest lessons of the pandemic education fallout for education policymakers, school district leaders, parents, teachers, and families.

Where did Canadian education authorities go wrong in responding to the global pandemic? How well did we prepare for such a calamity? Who really called the shots – provincial public health authorities? In hindsight, were schools closed for far too long? How well did we address the widespread “learning loss” and its collateral damage affecting students, teachers, families and schools? What have we learned and will we be better prepared the next time?