Five years into a $2.5-million seven-year Social Science and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) study known as “Thinking Historically for Canada’s Future,” funding support from 17 universities and 31 educational organizations has grown to exceed $8.6-million. Given that sizable investment, the whole project would benefit from more public scrutiny.

The ‘Thinking Historically’ project is the first major review of K-12 history and social studies in Canada since 1968. From my vantage point, it appears as if the project leader Carla Peck, a professor of social studies education at the University of Alberta, and her team are mostly focused on ‘perfecting teaching’ rather than carrying the torch in the ongoing debate over saving history as an endangered species in our schools. .

The project is headed and driven by education professors very much wedded to prevailing thinking and contemporary trends in North American social studies education. The goal is not to resurrect a shriveling subject discipline, but something else, as Peck told Brian Bethune in a recent University Affairs feature on dwindling history enrolments. Their goal, in her words, is to “understand how a critical historical thinking approach to teaching and learning history — and by critical, I mean analytical, not finding something wrong with everything — can support the development of critically minded citizens.”

Fine distinctions are important when it comes to delving into the state of history in today’s social studies curriculum. History as a subject in schools and universities is in crisis. Historica Canada, sponsors of the Canadian History Report Card, as well as most history department professors and high school teachers tend to favour “more history, taught better.” The key priority, reaffirmed since 2009 in the national Report Card reports, was to ensure that all high school students completed a required course in Canada’s history before graduation. Yet, even today, only five of our provinces meet that threshold. On the 2021 Canadian History Report Card, prepared by Samantha Cutrara, Alberta was awarded a D-, ranking last among the provinces and territories.

Many history professors and high school specialists question the effectiveness of the Historical Thinking approach in turning back the tide. That advancing tidal wave is most evident in the erosion of history-anchored curricula and in declining high school and university course enrolments.

Long before the late Peter Seixas established his Historical Thinking framework and Benchmarks of Historical Thinking, he described history as “a discipline cast adrift” the British Columbia social studies curriculum. The founder of the Thinking Historically movement, it should be noted, supported the centrality of history in a social studies curriculum.

History as a subject always seems to be imperiled, even in Ontario with its more robust tradition of providing it with preferred status in the social studies curriculum. The problem was flagged in 1995 by the late Bob Davis in Whatever Happened to High School History: Buring the Political Memory of Youth Ontario:1945–1995. In Ontario, where history formed part of the core curriculum, Davis discovered that enrolment went from accounting for 11.4 per cent of all classes in 1964 to a mere 6.6 per cent in 1982. In addition to losing ground, history and social studies became afflicted with what he aptly termed the “skills mania” afflicting our schools. Abandoning narrative history contributed to the decline by depriving our students of opportunities to engage with the larger national story and to develop a stronger sense of historical consciousness and collective memory.

History as a subject always seems to be imperiled, even in Ontario with its more robust tradition of providing it with preferred status in the social studies curriculum. The problem was flagged in 1995 by the late Bob Davis in Whatever Happened to High School History: Buring the Political Memory of Youth Ontario:1945–1995. In Ontario, where history formed part of the core curriculum, Davis discovered that enrolment went from accounting for 11.4 per cent of all classes in 1964 to a mere 6.6 per cent in 1982. In addition to losing ground, history and social studies became afflicted with what he aptly termed the “skills mania” afflicting our schools. Abandoning narrative history contributed to the decline by depriving our students of opportunities to engage with the larger national story and to develop a stronger sense of historical consciousness and collective memory.

Trilby Kent, the author of the 2022 book The Vanishing Past, concurs with Davis’s earlier assessment. Since the early 1970s, social history, Davis and Kent both point out, not only squeezed out older forms of history (political and economic) but contributed to fragmentation and sectarianism. In her book and in the Bethune article, Kent makes a persuasive case that such changes undermined “the sort of story that draws children to history,” Much of it was driven by the turn away from teaching engaging narrative history and towards critical-thinking-focused pedagogy. “By the 1990s, Kent observes, “‘learning how to learn’ had all but replaced learning content”

The Historical Thinking movement, launched by Seixas, never really gained as much traction among Quebec historians or history educators. History, memory and collective consciousness have always found resonance in French-speaking Quebec. From the late 1990s onward, history education researcher Jocelyn Létourneau eschewed what he termed “historical studies” and focused his research on how history shaped the historical consciousness of youth. Instead of working on perfecting how to teach history, he conducted surveys in 2000 and 2014 to ascertain how history conveyed a narrative and discovered that young Quebeckers exhibited a distinct and abiding sense of collective memory and consciousness.

More recently, University of Ottawa history education specialist Stéphane Lévesque has called into question the near exclusive emphasis on the “Seixas matrix” and pointed out the fact that “little policy has been informed by research about students.” Following the trail blazed by Létourneau, Lévesque and Jean-Philippe Croteau’s 2020 book, Beyond History for Historical Consciousness, examined what are termed “mythistories” based upon a 2016 survey completed by 635 high school students in Quebec and Ontario. While it was a relatively small sample study, it did break with the orthodoxy and made the case that history can be a potentially powerful force in shaping collective national identity. Teaching history, Lévesque and Croteau demonstrate, is not just about training students in historical thinking, but about “an essential cultural factor” – the “process of gaining narrative competence.”

More recently, University of Ottawa history education specialist Stéphane Lévesque has called into question the near exclusive emphasis on the “Seixas matrix” and pointed out the fact that “little policy has been informed by research about students.” Following the trail blazed by Létourneau, Lévesque and Jean-Philippe Croteau’s 2020 book, Beyond History for Historical Consciousness, examined what are termed “mythistories” based upon a 2016 survey completed by 635 high school students in Quebec and Ontario. While it was a relatively small sample study, it did break with the orthodoxy and made the case that history can be a potentially powerful force in shaping collective national identity. Teaching history, Lévesque and Croteau demonstrate, is not just about training students in historical thinking, but about “an essential cultural factor” – the “process of gaining narrative competence.”

One of Canada’s leading public historians, Trent University Canadian studies professor Christopher Dummitt, sees the writing on the wall. The current “presentist and potted-plant” to teaching history and social studies not only robs the subject of its broader appeal, but can be repelling if it is all cast within a history of victimhood and subjugation. The new national narrative will have no trace “of the fact that there really was a Canadian story amidst all this [oppressed] diversity,” he says. The implicit message, whether intended or not, is a story of an “illegitimate ‘settler colonial nation, steeped in a racist history.’”

History is also losing ground in the battle for students at our universities. The American Historical Association has identified enrolment decline in history courses as a critical problem and tracks the numbers, including trends in six Canadian universities. Prompted by fierce ‘culture war’ debates, the AHA is also surveying educators to assess its impact upon the teaching of U.S. history in American high school classrooms. From a peak enrolment in 2010–11, humanities enrolments at Canadian universities tumbled significantly until levelling out in 2016, according to by Alex Usher and his consulting firm Higher Education Strategy Associates. History took the biggest hit as students turned away from “narrative” humanities.

The decline in humanities enrolment, Usher points out, has reduced numbers back to where they were around 2000, when universities still had “a functioning humanities system.” The STEM, health, and business enrolments, which have been growing through the twenty-first century, have boomed even while history majors have declined from more than 15,000 to around 10,000.

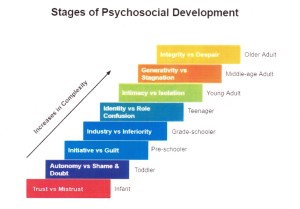

Forty years ago, one of Canada’s most respected education professors, Kieran Egan, took dead aim at the “expanding horizons” framework in his courageous 1983 essay, “Social Studies and the Erosion of Education.” To the shock of many contemporaries, he claimed that much of elementary social studies was based upon a “flawed” psychological theory, amounted to little more than “socializing children,” and eroded the foundations of sound education (Egan 1983, 1999).

Today social studies experts in the United States are beginning to reject “expanding horizons” as an overarching integrative framework. The most recent policy statement of the National Council for Social Studies, issued in 2017, put it this way: “The ‘expanding communities’ curriculum model of self, family, community, state, and nation is insufficient for today’s young learners. Elementary social studies should include civic engagement, as well as knowledge from the core content areas of civics, economics, geography, and history.”

History needs to be significantly upgraded in the holistic Alberta social studies curriculum and revivified elsewhere in Canada. A whole mélange of social studies courses is crowding out history in high schools in Alberta and in other provinces. It’s hard to imagine the Historical Thinking project making much of a difference, given the social studies focus of its director and its core Alberta supporters, exerting considerable influence in shaping its direction.

Focusing exclusively on teaching and learning historical thinking skills may well have obscured the essential role of history education in building “narrative competencies” in students and shaping our collective historical consciousness. More public advocacy where it counts is needed if we are ever to achieve the goal of ensuring that all students complete a high school course covering Canada’s history in all its diversity and complexity, reflecting a range of perspectives.

*An abridged version of Saving History in Canada’s Schools (ML Institute, April 18, 2024)

What would happen today if we asked senior high school students to “tell us the story of Canada” and conducted the same survey in every province/territory from coast-to-coast? Would our graduating students know the major turning points in our history and be able to provide a coherent response? Would the responses give credence to Dr. Chris Dummitt’s worst fears — eliciting a garbled explanation that Canada is an “illegitimate settler-colonial nation” harbouring sublimated racism? Or would a whole generation of students lack “narrative competency” and be unable to provide any kind of answer?