Snowstorms and icy roads signal the return of a hardy perennial — the public education debate over “snow days” and their impact upon students, families and communities. After almost two years of on-and-off COVID-19 school closures, the pandemic may have engineered an online evolution that spells the end of system-wide shutdowns at the first sign of inclement weather. Most, if not all, of the rationalizations for declaring “snow days” have disappeared.

When COVID-19 hit twenty-one months ago, schools closed and school systems pivoted to remote learning, combining traditional homework assignments and online classroom activities. Schools were closed in Canada from 8 weeks (British Columbia) to 20 weeks (Ontario) between March 2020 and mid-May 2021, and the gradual adoption of technology allowed students to learn from home.

“Continuous learning” enabled through technology and the internet survived the initial bumps, breakdowns and dislocations, mostly ironed out during the 2020-21 school year. Successful use and broader public acceptance of e-learning has now prompted many and perhaps a majority of North American school districts to do away with unscheduled days off for a range of natural calamities, including snow storms, hurricanes, flooding, heat waves, and epidemic diseases.

Southwestern Ontario’s largest school district, Thames Valley District School Board (TVDSB), responded by announcing the end of snow days. All 160 public schools in the London region, a mixed urban and rural district, are now required to provide online activities for their snowbound students. That board averaged about 5 to 7 snow day cancellations before the pandemic, roughly half the number claimed each year in rural Nova Scotia and the Maritimes.

The TVDSB’s associate director, Riley Culhane, says students, teachers and parents are ready to provide bridging education in “virtual classrooms.” Teachers have some discretion in deciding whether to offer “synchronous learning” or simply assign work to be completed at home. The continued use of e-learning days that were required during the pandemic, Culhane told the London Free Press, “just makes sense.”

The Ontario government pointed the way by encouraging school boards to prepare for shifts to remote learning, including during closures caused by adverse weather. That province’s back-to-school plan in August 2021 included a provision to enable districts to move smoothly to remote learning in the event of inclement weather. School boards are directed to develop inclement weather plans with local public health units, encompassing both heat days and storm days.

School districts in the United States have in recent years been gradually abandoning system-wide snow days, particularly since Ohio introduced e-learning days, enabled through “calamity day” plans, back in 2010. The proliferation of remote learning during COVID-19 accelerated the trend, particularly in states with severe weather rivalling that in the Maritimes.

A clear majority of American states are now on board in making the shift. An Education Week research survey, conducted in October 2020, reported that some 39 per cent of American school districts had converted snow days to remote learning days and 32 per cent were considering that change.

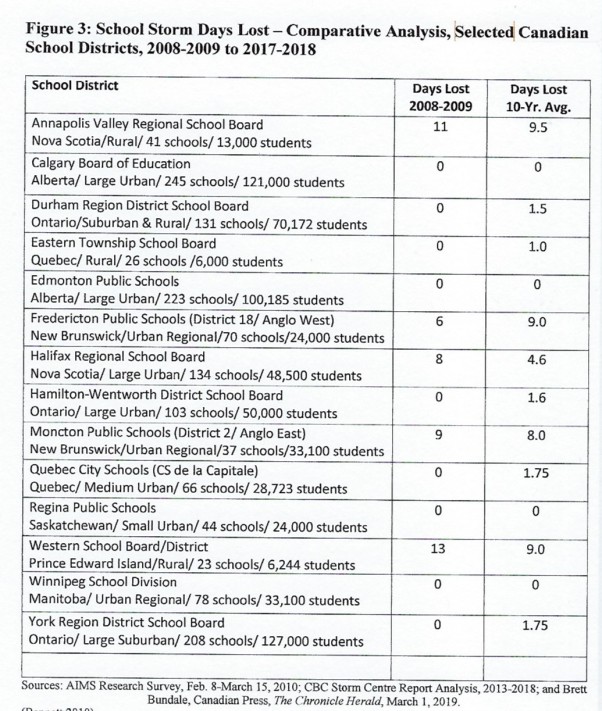

Public claims that snow days do not adversely affect student achievement hinge on the number and cumulative effect of days lost. While a January 2014 study covering 2003 to 2010 and undertaken for the National Bureau of Educational Research found minimal negative impact on achievement, that state averaged only 3 to 4 snow days per year and has amongst the lowest rates of student absenteeism.

Cancelling school as often as happens in Nova Scotia and the rest of Maritime Canada does have a detrimental effect on student learning. One relevant 2008 study, in Maryland public schools, found that as snow days piled-up that did have a cumulative effect, particularly at the elementary level, they did adversely affect student performance on state reading and math assessments.

Long before the pandemic, Nova Scotia students were paying an academic price for system-wide snow days. In the Maryland study, a high level of unscheduled closures – about 10 days (the Nova Scotia average), translated into 5 per cent fewer students meeting Grade 3 standards in reading and mathematics.

School authorities in the Maritimes have always defended calling snow days and giving everyone a ‘free day’ with no specific academic expectations. We now know that teacher contracts excusing teachers from reporting-in when schools are closed are a big and often unacknowledged factor. That was made abundantly clear when, in late November 2021, New Brunswick Education reversed its position on eliminating snow days.

When pressed by local media for an explanation, Education Department official Flavio Nienow came clean. Schools will continue to be closed on bad weather days, he said, because “in line with collective agreements, teachers are not required to report to work when schools are closed due to inclement weather.”

After all that’s happened and weeks of practice with remote learning, school districts are still clinging to past practice. While cancelling the odd day is understandable in larger cities where snow day cancellations number from 3 to 5 a year, it’s harder to justify cancelling school repeatedly when the lost teaching days accumulate and claims from one week to three weeks of instructional time.

Time will tell whether the pandemic will have achieved what educational policy-makers failed to accomplish – putting an end to the discharging of students and staff on inclement weather days.

What is the common and popular rationale for calling “snow days” without providing alternative learning programs? Why are school snow days still being called after two years of practice transitioning back and forth from in-person to online learning? Is it a matter of ingrained attitudes or impediments in the form of teacher contracts? What is the most viable solution to minimize the erosion of valuable instructional time?

The term “Snowcopalypse” was

The term “Snowcopalypse” was